Abstract

Objectives—To evaluate

the performance of liver and spleen stiffness measured by acoustic radiation

force impulse (ARFI) elastography for noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis

and esophageal varices in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus.

Methods—Two hundred

sixty-four participants, of whom 60 were healthy volunteers (classified as

stage 0), 66 were patients with chronic hepatitis B who had undergone liver

biopsy, and 138 were patients with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis, were enrolled

in this study. Median liver and spleen stiffness values (meters per second) from

10 successful measurements per participant were obtained. Patients with

cirrhosis were examined by upper endoscopy.

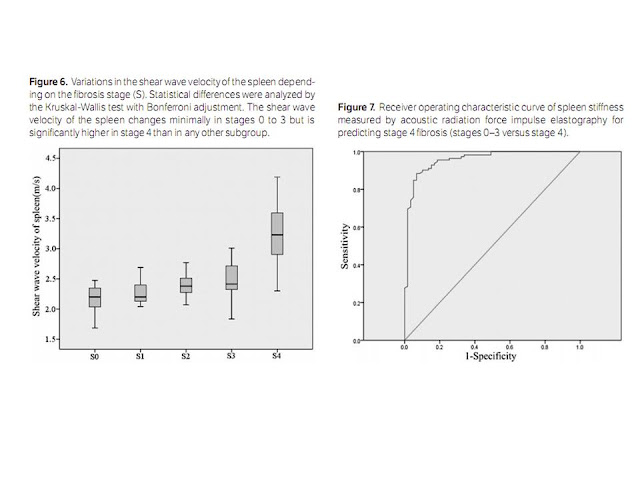

Results—Significant linear correlations were found between liver (Spearman ρ= 0.87; P < .001) and spleen (Spearman ρ = 0.76; P < .001) stiffness and the fibrosis stage. Liver and spleen stiffness values increased as fibrosis progressed; however, overlaps in liver stiffness were detected in stages 0 and 1 and 1 and 2, and overlaps in spleen stiffness were observed in stages 0 and 1, 1 and 2, and 2 and 3. Liver stiffness cutoff values were 1.69 m/s for predicting stage 3 or greater (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC] = 0.99) and 1.88 m/s for stage 4 (AUROC = 0.97). The spleen stiffness cutoff value was 2.72 m/s for stage 4 (AUROC = 0.96). Liver stiffness was not correlated with the varix grade, whereas a significant linear correlation (Spearman ρ = 0.65; P < .001) between spleen stiffness and the varix grade was found. The optimal spleen stiffness cutoff value for predicting varices was 3.16 m/s (AUROC = 0.83).

Conclusions—Liver and spleen stiffness values measured by ARFI elastography are reliable predictors of liver fibrosis. Spleen stiffness measured by ARFI can be used as a non-invasive method for determining the presence and severity of esophageal varices; however, evidence to support a similar role for liver stiffness is lacking.

Hepatitis B,

which is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), is a potential life-threatening

liver infection and the most serious type of viral hepatitis. As the World

Health Organization reported,1

approximately 2 billion people have been infected with HBV worldwide, and more

than 350 million people have chronic hepatitis B. In China

The

management and prognosis of chronic hepatitis B depend on the fibrosis stage.

To date, liver biopsy, an invasive technique, is still considered the reference

standard. However, its clinical application is limited because of its invasive

nature, potential severe complications, sampling errors, and interobserver and

intraobserver diagnostic discrepancies.4–6

In cirrhotic

patients, screening for esophageal varices is highly recommended and extremely

important because it is closely linked to the scheme of nonselective

beta-blocker therapy or endoscopic prophylaxis to prevent variceal bleeding.7 The

present screening method is endoscopy, which is performed every 2 to 3 years in

patients without esophageal varices, every 1 to 2 years in those with mild

varices, and annually in those with decompensated cirrhosis. However, this

method is invasive, expensive, and not easily accepted by patients.

For the

above-mentioned reasons, some noninvasive methods have been proposed to serve

as markers for evaluating of the degree of liver fibrosis and that of

esophageal varices, including serum markers,8–10

transient elastography,9–12

magnetic resonance elastography,13–15 and

acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography.10,16,17

Acoustic

radiation force impulse imaging10,16,18 is a

novel technology based on conventional B-mode sonography. An acoustic push

pulse excites the tissue and produces shear waves that spread away from the

tissue. The propagation of the shear waves can be measured, and their speed

depends on the elasticity of the tissue. Therefore, ARFI provides numeric

measurements of tissue stiffness as the shear wave velocity, expressed as

meters per second. Publications have shown that liver stiffness values

correlated well with liver fibrosis staging determined by liver biopsy.18,19

Spleen stiffness measured by ARFI elastography in patients with chronic liver

disease has also been previously reported.16,17

However, those studies focused mostly on patients infected with the hepatitis C

virus (HCV).

The aims of

this study were to evaluate the accuracy of liver and spleen stiffness measured

by ARFI elastography for noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis in patients

with chronic hepatitis B and to investigate whether liver and spleen stiffness

values are suitable predictors of the presence and severity of esophageal

varices.

Liver

and Spleen Stiffness Measurements

Liver and

spleen stiffness measurements were performed with an Acuson S2000 ultrasound

system equipped with virtual touch tissue quantification software (Siemens

Medical Solutions, Mountain View ,

CA

The interval

between these measurements and the liver biopsy that 66 of the participants

underwent ranged from 1 to 3 days (mean, 2.00 ± 0.84 days). Acoustic radiation

force impulse imaging was not immediately performed after biopsy because the

patients would not have been able to tolerate the pain caused by the biopsy and

scanning immediately after the procedure and because they needed to rest in the

dorsal decubitus position with a monitor for the first 6 hours.

The right

lobe was chosen because ARFI measurements of the right lobe are reportedly

potentially superior to those of the left lobe for diagnosis of liver fibrosis.20 A

point 2 to 3 cm under the liver capsule was chosen because a study of 3 points

under the liver capsule (0–1, 1–2, and 2–3 cm) found that the most reliable

liver elasticity values are obtained when ARFI measurements are made 2 to 3 cm

under the liver capsule.19

Discussion

The stage of

liver fibrosis can be quantified by ARFI elastography. Recent studies have

reported that measurement of liver stiffness using ARFI elastography is a

novel, accurate, and reliable noninvasive method for assessment of liver

fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease.21,22 As

liver fibrosis progresses, hemodynamic and pathologic changes can be found in

the spleen, especially in late stages of fibrosis. One study23 found

that the size of the spleen increased as liver fibrosis progressed and was more

apparent in late stages. The density of the spleen changes in patients with an

enlarged spleen because of tissue hyperplasia, fibrosis, and portal and splenic

congestion.12

Such changes in the spleen are mechanical properties that can be quantified by

ARFI elastography. Therefore, we tried to show that liver and spleen stiffness

values are useful predictors for evaluation of liver fibrosis in chronic liver

disease and to evaluate their performance in predicting the presence of

esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Moreover, to our knowledge, a study

assessing liver fibrosis and esophageal varices specifically in HBV-infected

patients has not been reported previously.

Our data clearly

showed that liver stiffness correlated well with fibrosis. The stiffness

increased with the fibrosis stage. However, overlaps were detected between

stages 0 and 1 and stages 1 and 2. Similarly, a study of 112 patients with

chronic hepatitis C found overlaps between the consecutive stages F1 and F2 and

stages F2 and F3 (METAVIR scores).18

Another study of 103 patients with chronic hepatitis of different etiologies

observed overlaps between stages F0 and F1 and stages F3 and F4 (METAVIR

scores).24

These findings suggest that overlaps between consecutive stages occur

regardless of etiology. For the healthy volunteers (stage 0), the mean liver

stiffness value in our study was 1.13 ± 0.12 m/s which is comparable to those

published so far: 1.13 ± 0.23 m/s in healthy volunteers and 1.16 ± 0.17 m/s in

stage F0 patients (METAVIR score)10 and

1.15 ± 0.21 m/s in another group of healthy volunteers.25 For

cirrhotic patients, the mean liver stiffness value was 2.50 ± 0.50 m/s,

comparable to 2.38 ± 0.74 m/s in 81 patients with HCV or HBV infection10 and

2.552 ± 0.7782 m/s in patients with HCV infection.18

We discovered

high predictive values of liver stiffness for stage 3 or greater and stage 4,

which were similar to the findings in a study of patients with chronic

hepatitis C18

and another study of patients with different etiologies.21 The

cutoff value for stage 3 or greater was 1.69 m/s, which was the same as the

value in a study by Toshima et al22

including 79 patients with different etiologies and similar to the value in a

study by Lupsor et al18

including 112 patients with chronic hepatitis C (1.61 m/s). The cutoff value

for stage 4 was 1.88 m/s, which was slightly higher than the value in the study

by Toshima et al22 (1.79

m/s) and lower than the value in the study by Lupsor et al18 (2.0

m/s).

This study

compared the mean spleen stiffness values measured by ARFI elastography among

fibrosis stages 0 to 4. There was a correlation between spleen stiffness and

fibrosis (Spearman ρ = 0.76; P < .001). The spleen stiffness values

for stages 0 to 3 did not statistically differ, whereas stage 4 had a

significantly higher mean value than any other stage. In our study, the mean

spleen stiffness value in the healthy volunteers (stage 0) was 2.17 ± 0.24 m/s,

which was slightly higher than the previously reported value of 2.04 ± 0.28 m/s

in 15 healthy volunteers17 and lower

than the previously reported value of 2.44 m/s in 35 healthy volunteers.26 The

mean spleen stiffness value in cirrhotic patients (stage 4) was 3.24 ± 0.44

m/s, which was slightly higher than the value of 3.10 ± 0.55 m/s in a study by

Bota et al.17

To date, only

2 reports have analyzed spleen stiffness for predicting cirrhosis. One17

showed a cutoff value of 2.55 m/s for predicting cirrhosis with a good AUROC

(0.91), and another16 showed

a cutoff value of 2.73 m/s (AUROC = 0.82). Our results showed a high predictive

value for the presence of cirrhosis (AUROC = 0.96), with the cutoff (2.72 m/s)

being higher than that in the first study and similar to that in the second.

In this

study, a combined analysis of liver and spleen stiffness measured by ARFI for

predicting the presence of cirrhosis revealed that the sensitivity and

specificity were higher when one of the methods in the combined analysis

yielded positive results than when only one method was used, and the

specificity was significantly elevated when both methods yielded positive

results.

In cirrhotic

patients, a severe consequence is portal hypertension, which is a contributing

factor to the formation of esophageal varices and a direct cause of variceal

hemorrhage. Publications have reported that liver stiffness measured using

1-dimensional transient elastography (Fibroscan) showed a statistically

significant association with the hepatic venous pressure gradient.27–29 Some

studies found that liver stiffness measured by 1-dimensional transient

elastography was correlated with the esophageal varix grade,30

whereas others showed that liver stiffness correlated with the presence of

varices but showed a weak correlation with the varix size31 or

none at all.27

Acoustic radiation force impulse elastography is a 2-dimensional elastographic

technique. To our knowledge, there have been no reports about the correlation

between liver stiffness measured by ARFI and the hepatic venous pressure

gradient or between liver stiffness measured by AFRI and the presence of

esophageal varices. Only 1 study17

reported a correlation between spleen stiffness measured by ARFI and esophageal

varices, in which the authors observed no significant differences in the mean

spleen stiffness values between patients with and without varices of between

those with different varix grades.

Our data on

this issue were confusing. We found a correlation between spleen stiffness and

the varix stage, and there was a significant difference between patients with

and without varices. We determined a cutoff value of 3.16 m/s for predicting

the presence of varices (AUROC = 0.83). We also found a significant difference

between grades 2 and 3, but unfortunately, we were not able to distinguish the

mean spleen stiffness values between grades 1 and 2. These results may be

explained by 3 possible reasons. First, endoscopy was not performed by the same

physicians, and the assessment of the varix grade was subjective. Second, not

all patients consented to undergo endoscopy and ARFI elastography on the same

day; the interval between spleen stiffness measurements and endoscopy ranged

from 0 to 30 days, whereas the longest interval in the report by Bota et al17

reached up to 6 months. Third, the distribution of patients according to varix

grades was unequal.

Our article

clearly suggests that there was no correlation between liver stiffness measured

by ARFI and the esophageal varix grade, and no significant difference was found

among the varix grades. The different results between liver and spleen

stiffness for assessment of varices may be explained by 2 possible reasons. First,

we discovered that the cirrhotic patients with elevated ALT and AST levels had

higher liver stiffness values than those with normal ALT and AST levels,

whereas the difference was not significant for the spleen stiffness values

between the patients with normal ALT and AST levels and those with elevated ALT

and AST levels. Some publications have reported a correlation between liver

stiffness values measured by ARFI and necroinflammation.18,21,32 These

reports indicate that elevated ALT and AST levels may affect liver but not

spleen stiffness values, which may be the major factor accounting for the

above-mentioned findings. Second, the unequal distribution of patients

according to varix grades may have led to different numbers in each subgroup.

___________________________

ARFI

elastography có thể định lượng được các giai đoạn của xơ hoá gan. Các nghiên

cứu gần đây đã thông báo rằng đo độ cứng gan bằng ARFI elastography là một

phương pháp mới không xâm lấn, chính xác và đáng tin cậy của xơ hoá gan ở những

bệnh nhân gan mạn tính. Khi xơ hoá gan tiến triển, thay đổi huyết động học và

bệnh lý có thể thấy được ở lách, đặc

biệt là trong giai đoạn cuối của xơ hoá. Một nghiên cứu cho thấy kích thước

của lách tăng khi xơ hoá gan tiến triển

và rõ hơn trong giai đoạn cuối. Mật độ của thay đổi lách ở những bệnh nhân lách

to vì tăng sản mô, xơ hóa, và sung huyết lách và tĩnh mạch cửa. Những thay đổi lách như vậy là những đặc tính cơ học định lượng được bởi ARFI elastography. Vì vậy,

chúng tôi đã cố gắng chứng tỏ các giá trị độ cứng gan và lách là các yếu tố tiên

đoán hữu ích cho việc đánh giá xơ hóa gan trong bệnh gan mạn tính và đánh giá

hiệu suất của chúng trong tiên đoán của dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản ở bệnh nhân chai

gan. Hơn nữa, theo chúng tôi được biết, nghiên cứu đánh giá xơ hoá gan và dãn

tĩnh mạch thực quản đặc biệt ở bệnh nhân nhiễm HBV chưa từng được báo cáo.

Dữ liệu của

chúng tôi rõ ràng cho thấy độ cứng gan tương quan với xơ hóa. Độ cứng tăng lên theo

giai đoạn xơ hóa. Tuy nhiên, có chồng lấp giữa giai đoạn 0 và 1 và giai đoạn 1

và 2. Tương tự như vậy, một nghiên cứu ở 112 bệnh nhân viêm gan C được tìm thấy

có trùng lặp giữa các giai đoạn liên tiếp F1 và F2 và giai đoạn F2 và F3 (tính

điểm METAVIR). Một nghiên cứu khác của 103 bệnh nhân viêm gan mạn với nguyên

nhân khác nhau có chồng lấp giữa giai đoạn F0 và F1 và giai đoạn F3 và F4 (tính

điểm METAVIR). Những phát hiện này gợi ý có xảy ra chồng chéo giữa các giai đoạn

liên tiếp bất kể do nguyên nhân nào. Đối với các tình nguyện viên khỏe mạnh

(giai đoạn 0), giá trị độ cứng gan trung bình trong nghiên cứu của chúng tôi là

1,13 ± 0,12 m/s so sánh với những công bố cho đến nay:1,13 ± 0,23 m/s ở người

tình nguyện khỏe mạnh và 1,16 ± 0,17 m/s ở bệnh nhân giai đoạn F0 (tính điểm METAVIR) và

1,15 ± 0,21 m/s trong một nhóm khỏe mạnh tình nguyện. Đối với bệnh nhân chai gan,

giá trị trung bình độ cứng gan là 2,50 ± 0,50 m/s, tương đương với 2,38 ± 0,74

m/s ở 81 bệnh nhân nhiễm HCV hoặc HBV và 2,552 ± 0,7782 m/s ở những bệnh nhân nhiễm

HCV.

Chúng tôi phát

hiện ra giá trị tiên đoán cao của độ cứng của gan ở giai đoạn 3 hoặc cao hơn và

giai đoạn 4, tương tự như phát hiện trong một nghiên cứu khác ở bệnh nhân viêm

gan C mạn, và một nghiên cứu khác nữa của bệnh nhân có các nguyên nhân khác. Giá

trị cutoff cho giai đoạn 3 hoặc cao hơn là 1,69 m/s, tương tự như giá trị của

Toshima và cs với 79 bệnh nhân với các

nguyên nhân khác nhau và tương tự như giá trị của Lupsor và cs gồm 112 bệnh

nhân viêm gan C (1,61 m/s ). Giá trị cutoff cho giai đoạn 4 là 1,88 m/s, cao

hơn một ít so với nghiên cứu của Toshima và cs (1,79 m/s) và thấp hơn trong

nghiên cứu của Lupsor và cs (2,0 m/s).

Nghiên cứu này

nhằm so sánh các giá trị độ cứng lách trung bình đo bằng ARFI elastography giữa các

giai đoạn xơ hóa 0-4. Có tương quan giữa độ cứng lách và xơ hóa (Spearman ρ =

0,76; P <.001). Giá trị độ cứng lách cho các giai đoạn 0-3 không có khác biệt

thống kê, trong khi giai đoạn 4 có giá trị trung bình cao hơn có ý nghĩa hơn

bất kỳ giai đoạn nào khác. Trong nghiên cứu của chúng tôi, giá trị độ cứng lách

trung bình của các tình nguyện viên khỏe mạnh (giai đoạn 0) là 2,17 ± 0,24 m/s,

đó là hơi cao hơn giá trị báo cáo trước đây của 15 người tình nguyện khỏe mạnh

là 2,04 ± 0,28 m/s và thấp hơn so với giá trị của 35 người tình nguyện khỏe

mạnh là 2,44 m/s đã báo cáo trước đó. Giá

trị độ cứng lách trung bình ở bệnh nhân chai gan (giai đoạn 4) là 3,24 ± 0,44

m/s, cao hơn so với giá trị 3,10 ± 0,55 m/s trong một nghiên cứu Bota và cs.

Cho đến nay, chỉ

có 2 báo cáo đã phân tích độ cứng lách để tiên đoán xơ gan. Một nghiên cứu cho

giá trị cutoff là 2,55 m/s để dự đoán xơ

gan với một AUROC tốt (0,91), và bài khác cho giá trị cutoff là 2,73 m/s (AUROC

= 0,82). Kết quả của chúng tôi cho giá trị tiên đoán cao cho sự hiện diện của chai

gan (AUROC = 0,96), với cutoff (2,72 m/s) cao hơn nghiên cứu đầu tiên và tương

tự như lần thứ hai.

Trong nghiên cứu

này, một phân tích kết hợp của độ cứng gan và lách đo bằng ARFI để tiên đoán chai

gan cho thấy rằng độ nhạy và độ đặc hiệu cao hơn khi phương pháp

phân tích kết hợp mang lại kết quả dương tính hơn là chỉ có một phương pháp được sử dụng, và độ

đặc hiệu tăng đáng kể khi cả hai phương pháp mang lại kết quả dương tính.

Ở bệnh nhân chai

gan, hậu quả nghiêm trọng là cao áp tĩnh mạch cửa, là một yếu tố góp phần vào

sự hình thành dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản và là nguyên nhân trực tiếp gây xuất

huyết dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản. Y văn cho thấy đo độ cứng gan bằng cách

sử dụng 1-D elastography thoáng qua (FibroScan) có kết hợp có ý nghĩa

thống kê với gradient áp lực tĩnh mạch gan [hepatic venous pressure gradient]. Một số nghiên cứu thấy rằng độ

cứng gan đo bằng FibroScan có tương quan với giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản,

trong khi những khảo sát khác cho thấy độ cứng gan liên quan với có dãn tĩnh

mạch thực quản, nhưng có tương quan yếu với kích thước dãn tĩnh mạch hoặc không

có tương quan nào hết. Đo đàn hồi ARFI

là kỹ thuật đo đàn hồi 2 chiều. Theo chúng tôi biết, chưa có báo cáo về tương

quan giữa độ cứng gan đo bởi ARFI và gradient áp lực tĩnh mạch gan hoặc giữa độ

cứng gan đo bằng AFRI với hiện diện của dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản. Chỉ có 1 báo

cáo về tương quan giữa độ cứng lách đo bằng ARFI và dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản,

trong đó các tác giả quan sát thấy không có sự khác biệt đáng kể trong giá trị

độ cứng lách trung bình giữa các bệnh nhân có và không có dãn tĩnh mạch và giữa

những người có giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản khác nhau.

Dữ liệu của

chúng tôi về vấn đề này là khó hiểu. Chúng tôi thấy có tương quan giữa độ cứng

lách và giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản, và có khác biệt có ý nghĩa giữa bệnh nhân có và

không có dãn tĩnh mạch. Chúng tôi xác định một giá trị cutoff là 3,16 m/s để dự

đoán sự hiện diện của dãn tĩnh mạch (AUROC = 0,83). Chúng tôi cũng tìm thấy có

khác biệt đáng kể giữa giai đoạn 2 và 3, nhưng thật không may, không thể phân

biệt các giá trị độ cứng lách trung bình giữa giai đoạn 1 và 2. Những kết quả

này có thể được giải thích bởi 3 khả năng. Một, nội soi không được thực hiện bởi

các bác sĩ, và việc đánh giá giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản là chủ quan. Thứ

hai, không phải tất cả các bệnh nhân đồng ý được nội soi và ARFI elastography

trong cùng một ngày, khoảng thời gian giữa đo độ cứng lách và nội soi khoảng

0-30 ngày, trong khi khoảng thời gian dài nhất trong báo cáo của Bota và cs là

6 tháng. Thứ ba, phân bố của bệnh nhân theo giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản không

đồng đều.

Bài báo này của

chúng tôi, cho thấy rõ không có mối tương quan giữa độ cứng gan đo bằng ARFI với

giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản, và không có khác biệt có ý nghĩa giữa các

giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản. Các kết quả khác nhau giữa độ cứng gan và

lách trong đánh giá dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản có thể được giải thích bằng 2 khả

năng. Một, chúng tôi phát hiện ra rằng các bệnh nhân chai gan với mức ALT và

AST cao có giá trị độ cứng gan cao hơn những người có mức ALT và AST bình

thường, trong khi khác biệt giá trị độ cứng lách không có ý nghĩa giữa các bệnh

nhân có mức độ ALT và AST bình thường và những bệnh nhân có ALT và AST cao. Một

số báo cáo cho thấy có tương quan giữa giá trị độ cứng gan ARFI và viêm hoại tử

[necroinflammation]. Các báo cáo này chỉ ra rằng mức ALT và AST cao có thể ảnh

hưởng đến gan, nhưng không ảnh hưởng đến giá trị độ cứng lách, có thể là nhân

tố chính cho phát hiện đề cập ở trên. Thứ hai, phân bố các bệnh nhân không đồng

đều theo giai đoạn dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản có thể dẫn đến khác biệt về số lương

trong mỗi phụ nhóm.

Để kết luận, giá

trị độ cứng gan và lách đo bằng ARFI elastography là yếu tố tiên đoán đáng tin

cậy của xơ hoá gan, đặc biệt là đối với những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ cao hoặc

không sẵn sàng để sinh thiết gan. Độ cứng lách có thể được dùng như một phương

tiện không xâm lấn để tiên đoán có và giai đoạn của dãn tĩnh mạch thực quản và

cũng có thể có giá trị cho các bệnh nhân từ chối làm nội soi. Hơn nữa, các

nghiên cứu sâu hơn về độ cứng gan và lách nhằm đánh giá xơ hoá gan và dãn tĩnh

mạch thực quản trong một dân số lớn hơn đã được lên kế hoạch.